Using the WPA "Slave Narratives" in the High School Classroom

Formerly enslaved Texan, Wes Brady

First-hand accounts support much of what goes down in my classroom - especially in my 10th-grade honors United States history class (naturally), but also in my more advanced course (it’s a college-level class, really) on the American Civil War. My students figure out pretty quickly that primary sources offer a window through which we can peer into the worlds of historical actors. My students get this from day one and by the time they graduate, the kids are adept at reading and contextualizing primary sources. Lately, I have been focusing more and more on selections from Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. The so-called “Slave Narratives,” collected from 1936 to 1938 as part of the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, was an effort undertaken by the Roosevelt administration to catalogue the experiences of formerly enslaved black Americans who recalled the institution in its final days. All together, these narratives number some 2000 interviews – most transcribed as written documents, some recorded. You can find them at the Library of Congress website - Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938. The recordings are also linked to the LOC website - Voices Remembering Slavery: Freed People tell Their Stories. As you might guess, my students find these sources fascinating.

Historians have long noted how we might approach these narratives with at least some degree of caution. As such, it’s important to address a number of things in the classroom. Something that often comes up when I first introduce primary documents (in the 9th grade…) is that the kids tend to take them entirely at face value. Afterall – these are historical actors who experienced the history first-hand. But once we discuss bias and perspective and all that they begin to look for context and motive and any number of influential variables and analyze accordingly. With the slave narratives, the passage of time is a pretty obvious point to consider. Distance removed from a particular event might have distorted memories (though one might suggest that salient memories would likely tend to stand out among others). In addition, those interviewed were young children when they experienced slavery. Is it possible that this would make a difference? Maybe – maybe not. But it’s worth asking. Finally, looking at historical actors’ memories of the distant past brings up questions concerning how we remember things – and why we remember things the way we do...perhaps to help us better understand and come to terms with the present. Keep in mind that I do not have definitive answers here – but the questions are important to engage all the same.

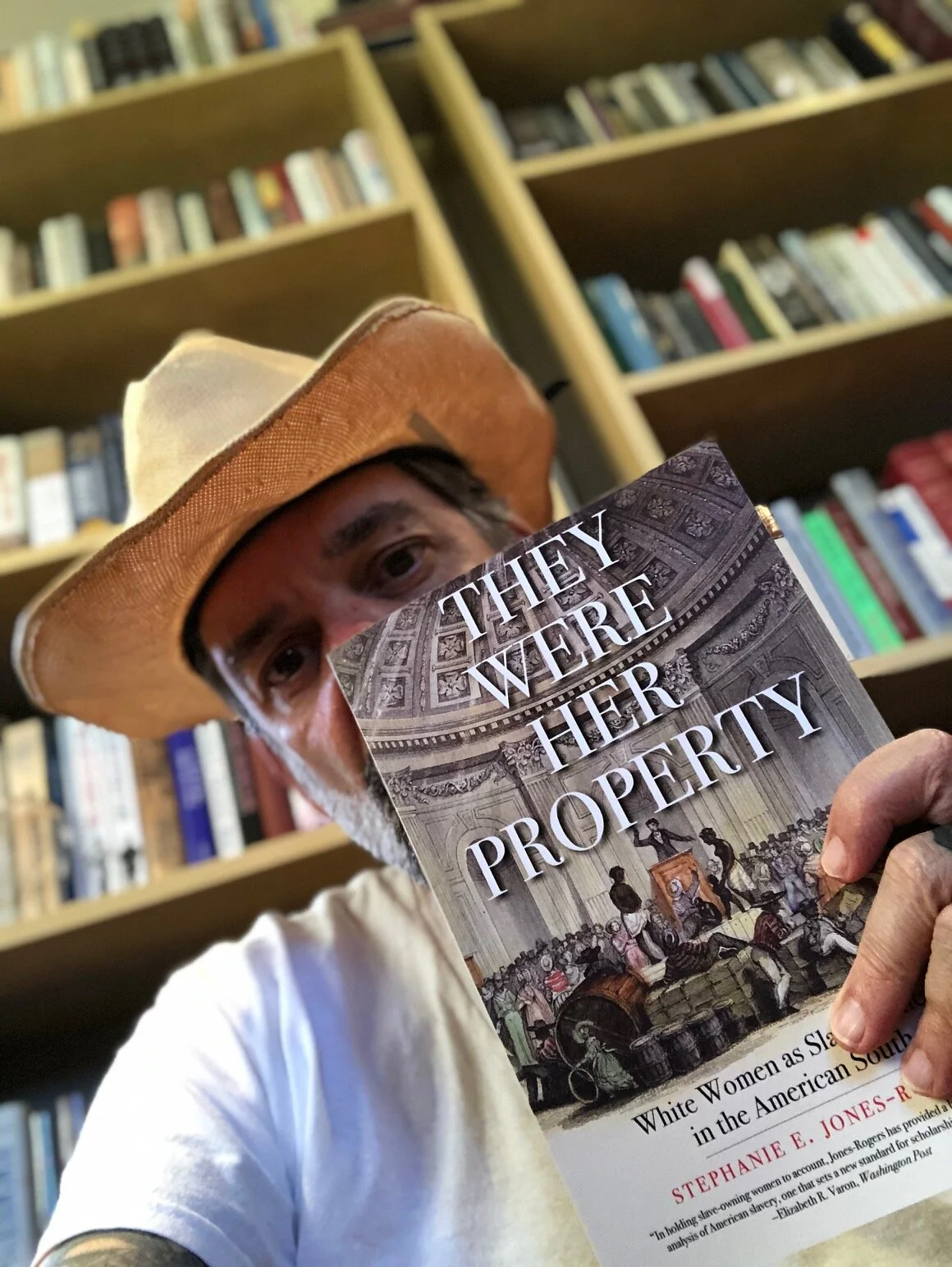

Do yourself a favor and read this.

And…just because we approach a set of documents with caution does not mean that they fail to reveal historical truths – or at least elements of the truth (or Truth, depending on where you stand on such things…). Like with any document set, we look for themes that suggest historical accuracy. Also, we look for corroborating evidence from other sources. In this case we might compare reminiscences of slavery with evidence prior to 1865. I recently read (and plan to assign excerpts from) They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers. Here, the author did a first-rate job challenging a conventional view suggesting households were monolithically patriarchal. She further reveals in a convincing way that women were not merely complicit bystanders on the margins of the peculiar institution. Jones-Rogers enlists tons of supportive evidence for sure – both from the period before 1865 as well as the slave narratives from the 1930s. But even so, we must acknowledge different takes. For the scholarship she challenges also draws testimony from the narratives. Different conclusions drawing from the same sources support the notion that historians are always in a dialogue, and that well-mined resources can continue to yield additional layers in the historical narrative. Sometimes it simply means asking different questions of the historical record…something I strongly encourage.

A few final thoughts that underscore an unsavory chapter in American history, but one that students should understand. Naturally, I discuss these things at length with my kids before we take on the Slave Narratives. First, more often than not, there was a clear power imbalance between interviewer and interviewee. Think of the context in which these interviews took place: the Jim Crow South. Most of the interviewers were white, and under the circumstances, black folks were well aware of the potential danger of stepping out of line, so to speak. Does this mean that interviewees might have tailored their responses accordingly? Perhaps. Second, the interview transcriptions are written in dialect – and might indeed reflect the biases of the interviewers. Many of my students in the past have found this offensive – almost as if the transcriptions were meant to caricature the formerly enslaved people. What, I ask, can we learn by looking the physical transcriptions themselves? Finally – the use of the n word. This has been a real tough one for me. The interviewees use the word liberally. But let’s be honest, it’s a word I don’t want my students using under any circumstances. But at the same time, I am not a fan of sanitizing history. So, we read their words silently, keeping in mind the contextual framework of the period.

The goal of all of my classes is to explore history from the perspectives of as many people as I can possibly fit into a school year. These voices are only some among many that I challenge my kids to engage. I never knew the Slave Narratives existed until college. I wonder if other high school teachers out there use them in class. I would love to hear from you if you do – or even if you don’t. I would love to discuss why.

With compliments,

Keith