Death and the Case for Bureaucracy

Okay friends – show of hands…who among us loves a big fat bureaucracy? Let’s be honest – bureaucracies have a bad reputation for leaning unnecessarily Byzantine, and traditionally, Americans are suspect of bottlenecking decision-makers who often fall short when dealing with societal challenges. Still…while some folks tend to criticize labyrinthian regulations and red tape, Civil War historian Stephen Berry takes a different approach. In his latest book from UNC Press, Count the Dead: Coroners, Quants, and the Birth of Death as We Know It, Berry attributes modern-day human longevity (twice that of recent history) not to so much to medical advances, but rather…to bureaucracies. It was the bureaucrats, the first to bother to count the dead, he argues, that made all the difference.

A must-have.

To be fair, he does say that medicine had something to do with it. But without data-collecting bureaucrats, Berry suggests, there would have been no way to inform and direct the leading minds of the day toward creating the means necessary to increase the average lifespan. Barry offers three points of argumentation: “If we count the dead, we might have better public health. If we count the dead, we might have fewer or “better” wars. If we count the dead, we might strike stronger blows for social justice.” (84)

So, my initial reaction was to snicker at the fact that I owe my life expectancy (and relative safety, as it turns out…) to a bean-counting paper-pusher. (8) But I gotta admit that homie makes a compelling argument. In a clear and concise manner (the book is very accessible and only 92 pages – you could knock it out in an afternoon…), Berry argues that data tell a story – a story that might not have been in mind upon the collection of said data. (24) Hmmmmm….so those who use data to explain some death-causing phenomenon like disease, war, or poverty might provide much needed information to help prevent the phenomenon in the present ot future. Okay, I’ll buy that. It seems fairly easy to agree with criminology professor and advocate for statistical analysis Geoffrey Alpert: “if we don’t know the data, how do we identify the problem?” (82)

But beyond Berry’s enthusiastic embrace of data and those who collect, there are two themes in this book that I plan on bringing to the classroom.

First, bureaucracies are neither good nor bad, they just are. And like any institution, people can bend them to serve a purpose. Now, that purpose may indeed be nefarious…but it might just as likely work towards the greater good – as subjective as that is. In the classroom this book could be useful to defuse preconceived notions about the efficacy of government agencies. One might say that individuals harness institutions to serve needs and agendas – a safe argument. I use much the same approach when discussing the United States Constitution, especially to offer a counter argument to those who claim it is irredeemably racist. None other than the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass himself claimed that if people bent the meaning of the Constitution to serve slaveholders, they could just as easily bend it to serve the cause of freedom and justice. It seems that institutions could function in much the same manner.

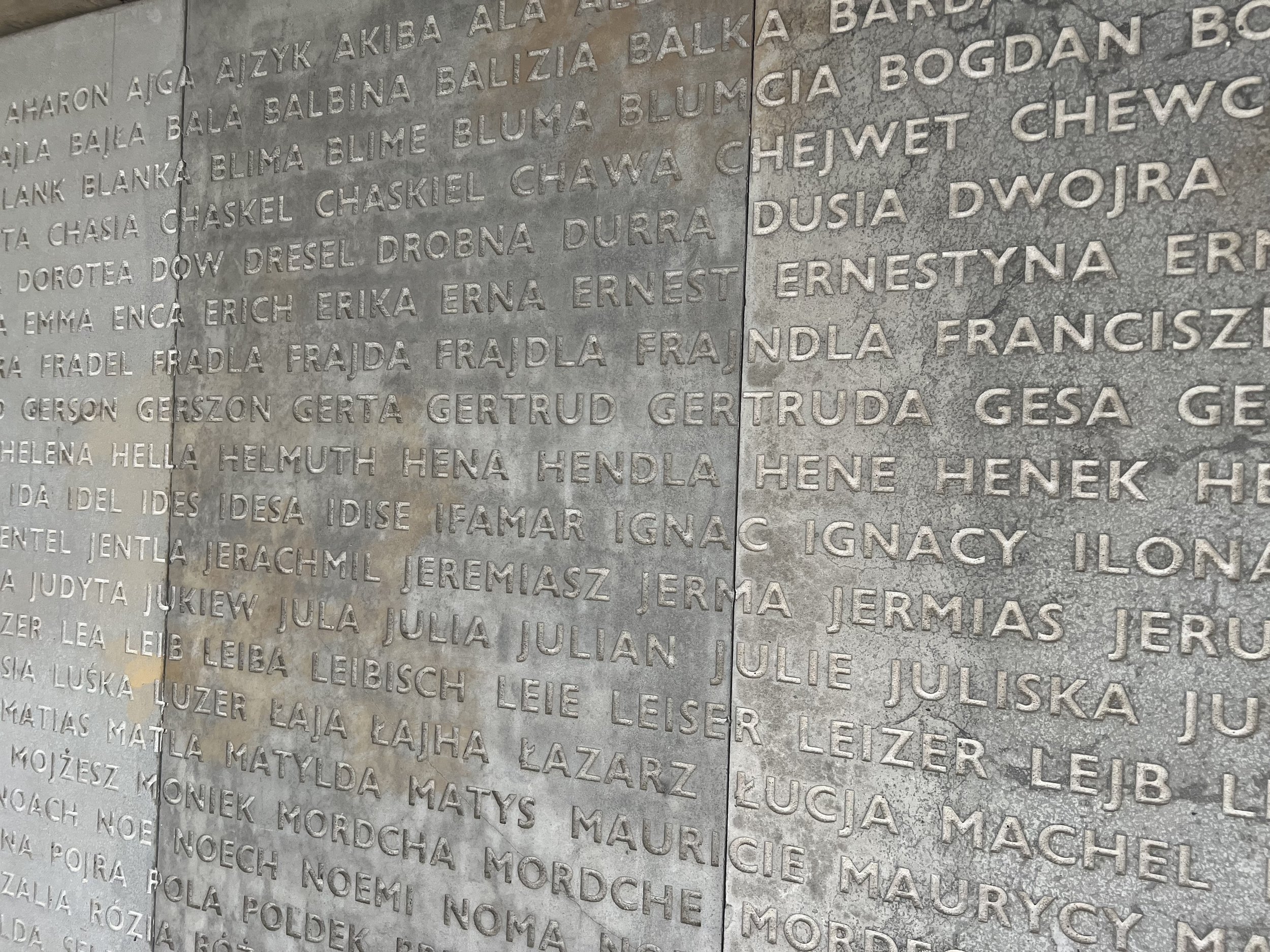

Naming the dead at Belzec

Second, Berry insists that in order to establish historical accountability we must name both the killed and the killers. With this I agree unequivocally. While of course it is not always possible to name everyone – identifying individuals offsets the tendency to distill sweeping episodes of death: epidemics, wars, genocides – to mere abstractions. I have recently experienced such efforts in a tangible way. Having just visited the sites of Nazi extermination camps in Poland, I was particularly struck by the understated memorialization, especially that which included the names of those who perished, whether individuals on lists at the Radegast Train Station or the lists of surnames on the memorial walls at Belzec – naming people adds human agency to the story.

I look forward to including this book in my classroom discussions during the upcoming school year. And I am quite certain I will return to it time and again. For a thin volume there is a ton of great stuff within these pages…everything from a comparison of pandemics stretching back to antiquity to the problematic nature of the United States Census. I’ll be back here to discuss when the conversation turns to numbers and to the dead – which it invariably will.

With compliments,

Keith